The Great Migration

By Josna Rege

An axiom of the U.S. national discourse is that we are—with the exception of Native Americans—a nation of immigrants. But this oft-repeated aphorism has another glaring exception: the Africans taken from their homes against their will, made to travel the deadly Middle Passage, and enslaved in America. They were not immigrants fleeing persecution or looking for “a better life;” their imaginations were not captured by the American Dream. On the contrary, better lives for the European settlers were achieved on their backs, and the freedom of the American Dream depended in large part on their lack of freedom.

Migrants by choice

So yes, Africans were migrants, but not of their own accord. However, there is a migration that they embarked on by choice—one that, strangely, is often unacknowledged when telling the American story—and that is the Great Migration.

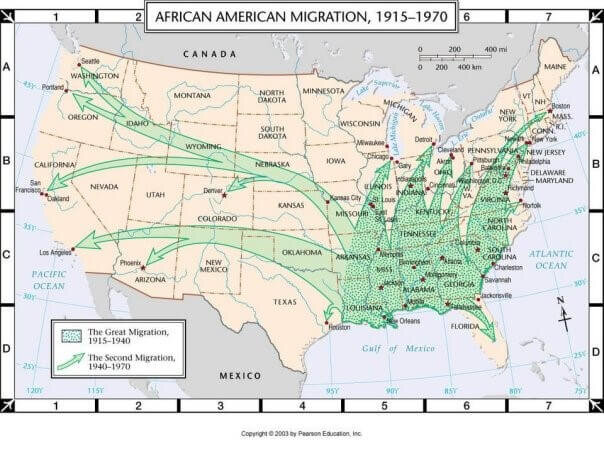

The Great Migration, which started as a trickle in 1916, grew to a flood over the next 6 decades and encompassed the movement of more than 6 million African Americans from the Jim Crow South to cities in the North. As Isabel Wilkerson, author of The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration, wrote in Smithsonian Magazine,

By the time it was over, in the 1970s, 47 percent of all African-Americans were living in the North and West. A rural people had become urban, and a Southern people had spread themselves all over the nation.

Despite the end of the abhorrent institution of slavery after the Civil War, despite the declaration that African Americans were U.S. citizens with the right to vote, Reconstruction had been sabotaged and African

Americans had been systematically impoverished, disenfranchised, and marginalized from mainstream American society. White supremacy was rampant, and a reign of terror was maintained by groups like the Ku Klux Klan and supported by state governments.

According to the NAACP, thousands of lynchings took place between 1882 and 1968, mostly of Blacks, and mostly in the South. During that period, there were 581 lynchings in Mississippi, 531 in Georgia, and 493 in Texas alone. Life became unbearable, and eventually African Americans, prevented from declaring themselves at the ballot box, had had enough. They voted with their feet, and left. Building their lives anew in new environments required strength, courage, and creativity, all of which they had in abundance.

The Great Migration led to the transformation of American society in many ways: increased urbanization, a cultural renaissance in almost every arena, and people’s movements—notably the Black Power and Civil Rights movements, which led to the end of Jim Crow segregation and, in time, to profound political change for all Americans. Although abandoned as home, the South was not forgotten. Like many migrants, African American families in the North made the pilgrimage back whenever they could to visit their children’s grandparents and their extended families, back to what Farah Jasmine Griffin, in her first book Who Set You Flowin’: The African American Migration Narrative, has called “the site of the ancestor.”

Musical migrations

One of the most dramatic impacts of the Great Migration occurred in the world of music. Chess Records in Chicago became one of the centers of the blues as it migrated from places like the Mississippi Delta with musicians like McKinley Morganfield—better known as the late, great Muddy Waters, without whom rock-’n-roll as we know it would not exist. Here’s Muddy Waters in an inimitable performance of Got My Mojo Working, with the help of Sonny Boy Williamson on harmonica and Willie Dixon on bass, both of whom were also Mississippi natives.

As in Chicago, Seattle’s African American population created a vibrant and enduring new music scene. Seattle’s Jackson Street jazz clubs survived the Great Depression and were in full swing in the 1940s, when the second wave of the Great Migration brought workers to the region’s shipyards, military bases, and airplane-manufacturing industry. Near the end of World War II, 16-year old Ernestine Anderson arrived with her family from Houston. While still at Garfield High School, she found herself performing in “Bumps” Blackwell’s Junior Band with fellow teens Ray Charles (recently arrived on a bus from Florida) and Quincy Jones (whose family migrated from Kentucky via Chicago). In an interview with the Seattle PI, Jones recalled, "Seattle in the 1940s was like New Orleans…. Every club would be open 24/7. We'd work all the time, 7 to 10 at the white tennis club and back downtown to bebop till 3 in the morning.” Here’s Ernestine Anderson singing Miles Davis’s All Blues.

The “whites-only” designation of Seattle’s high-paying musical venues led to some reverse migrations, sending many local Black jazz musicians out of town in search of a living wage. Ernestine Anderson recorded her first album in Sweden and later lived in London for a couple of years. In Shanghai, members of a Seattle jazz band not only made good money; they also reported that “they were treated with respect for the first time in their lives.”

The first of many steps

While leaving the South opened up new opportunities for migrants, it was no panacea. Seattle jobs that had been filled by African Americans during the two world wars either disappeared or were given to whites at war’s end. African American historian Quintard Taylor notes that, in Seattle “…blacks remained concentrated in menial occupations. In 1910, 45% of black males were servants, waiters, and janitors; by 1940, 56% were in that category. Black women fared worse: in 1910, 84% were domestic or personal servants; by 1940, 84% were still in that category.” And during the first half of the 20th century, residential discrimination in Seattle worsened as redlining and restrictive real estate covenants confined the city’s Black residents primarily to two neighborhoods – today’s Central District and International District.

Over time, civil rights activism and diplomacy have led to meaningful policy change – in housing, education, voting rights, and labor. In the world of music, Seattle’s racially segregated musicians’ unions finally merged in 1958, ending more than 50 years of contentious separation. Here, as in other northern and western cities, the Great Migration was only a first step on a long and unfinished road to equal opportunity.

***

This is the 6th in a series of EQUITY BLOGS that explores the contexts of longstanding disparities in the health and well-being of King County residents. In addition to helping us understand the root causes of some disparities, the blogs show how tightly history is woven into our lives and our futures. They also acknowledge the rich variability of responses within and across groups and generations, from strength and resilience to lasting harm embedded in policy and everyday life.

Initially posted at Tell Me Another on April 10, 2019, the original version of “G is for the Great Migration” by Josna Rege was part of a month-long “Blogging from A to Z Challenge” on the theme, Migrants, Refugees, and Exiles. This version has been edited for Communities Count audiences. Added sections in italics.

LINKS

Mapping the Great Migration offers access to interactive maps, charts, and data tables about the movement of African Americans out of the South.

America’s Great Migrations is a project of the University of Washington’s Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium that links to articles, interactive tools, details of Washington and Seattle migration histories, and a database of more than 700 books and articles.